|

Housingclick to view |

|

Health Careclick to view |

|

Child Care and Educationclick to view |

|

Technologyclick to view |

|

Foodclick to view |

|

Taxesclick to view |

|

Transportationclick to view |

||

Impact on ALICE • Child Care

- Family-based care: Child care provided in a home setting for one or more unrelated children. Most states have regulatory guidelines for family child care homes based on the number and ages of children they serve as well as the number of hours their business operates. This type of care is unregulated in some states; is regulated to certain standards in many others; and, in a few states, is even licensed or included in state educational quality rating systems. But in most states, family-based child care is not held to the same standards for health, safety, and current or future learning outcomes as center-based care.8

- Center-based care: Child care provided in nonresidential group settings, including public or private schools, churches, preschools, day care centers, or nursery schools. Center-based care is usually licensed, and many are accredited by state or nonprofit early childhood organizations.9

- Preschool: Programs that provide early education and care to children before they enter kindergarten, typically from ages two-and-a-half to five years. Preschools may be publicly or privately operated and may receive public funds. They may be housed in schools, faith-based settings, or commercial spaces.

- Family-based care: Child care provided in a home setting for one or more unrelated children. Most states have regulatory guidelines for family child care homes based on the number and ages of children they serve as well as the number of hours their business operates. This type of care is unregulated in some states; is regulated to certain standards in many others; and, in a few states, is even licensed or included in state educational quality rating systems. But in most states, family-based child care is not held to the same standards for health, safety, and current or future learning outcomes as center-based care.8

- Center-based care: Child care provided in nonresidential group settings, including public or private schools, churches, preschools, day care centers, or nursery schools. Center-based care is usually licensed, and many are accredited by state or nonprofit early childhood organizations.9

- Preschool: Programs that provide early education and care to children before they enter kindergarten, typically from ages two-and-a-half to five years. Preschools may be publicly or privately operated and may receive public funds. They may be housed in schools, faith-based settings, or commercial spaces.

- Affordability: Quality child care is very costly, and increases with the number of children in a family. In 2016, 32 percent of parents with difficulties finding child care said cost was the primary challenge:13

- Quality: There is a huge variation in the quality of care, which impacts a child’s ability to reach developmental milestones.

- Assistance: Eligibility for state child care assistance is tied to income, and many ALICE families do not qualify.

- Availability: Child care center hours often fall short of the coverage needed by working parents.

- Proximity: Just over half of low-income parents of children under age six reported that they have good choices for child care in their community, compared to almost 70 percent of high-income parents.14

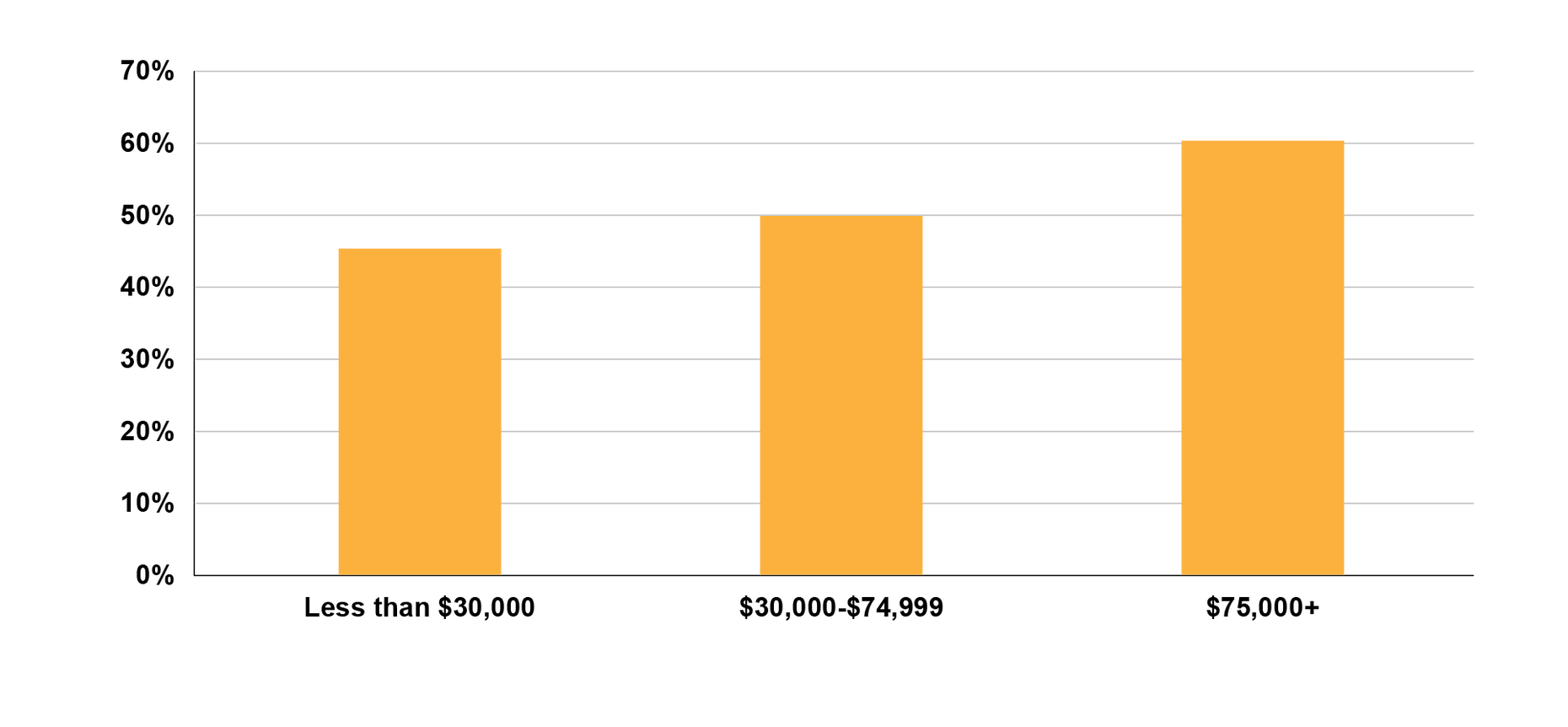

Nationally, child care attendance remains closely tied to income. In 2017, 3- to 5-year-olds in families with income above $75,000 were 30 percent more likely to be enrolled in pre-K or preschool programs than those with income of less than $30,000. There are also differences by race/ethnicity, with Hispanic children less likely to be enrolled in center-based care compared to other groups.15

Percent of Children Enrolled in Early Learning Programs by Household Income, U.S., 2017

Sources: Child Trends' original analysis of data from the Current Population Survey, October Supplement, 1994-2017 Appendix 2; Child Trends. (2014). Early childhood program enrollment

What do families do if they cannot access child care or preschool?

Quality child care or preschool function as cornerstones to a child’s healthy development, as well as to a family’s income stability and growth. Yet many ALICE families struggle to obtain this essential need, for reasons including affordability, quality, assistance, and availability. Here are strategies that different ALICE families try:

Seek Less Costly Care

One option is to choose a home-based care center, with a lower average cost compared to center-based care. Nationally in 2017, the average cost of home-based care was $8,729 annually for a toddler, compared with $10,096 for center-based care.16 However, home-based care centers may have different regulatory requirements and can vary greatly in terms of quality.

One option is to choose a home-based care center, with a lower average cost compared to center-based care. Nationally in 2017, the average cost of home-based care was $8,729 annually for a toddler, compared with $10,096 for center-based care.16 However, home-based care centers may have different regulatory requirements and can vary greatly in terms of quality.

Pay More than Family Budget Allows

Another choice may be to pay more than is affordable for child care, in order to access higher-quality care or extended coverage (“wraparound care”). This choice can solve the immediate need of accessing quality care, but can also have a long-term ripple effect across many aspects of family life:

Another choice may be to pay more than is affordable for child care, in order to access higher-quality care or extended coverage (“wraparound care”). This choice can solve the immediate need of accessing quality care, but can also have a long-term ripple effect across many aspects of family life:

Find a Publicly Funded Preschool

A public preschool can offer significant cost savings and improve learning outcomes.22 However, there are downsides to this option, related to funding, quality, and scheduling.

A public preschool can offer significant cost savings and improve learning outcomes.22 However, there are downsides to this option, related to funding, quality, and scheduling.

Seek Assistance

You could seek state child care assistance, provided you meet eligibility requirements. Eligibility for child care is tied to family income: in most states, it is approximately 200 percent of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL), and as high as 250 percent in some states.26

You could seek state child care assistance, provided you meet eligibility requirements. Eligibility for child care is tied to family income: in most states, it is approximately 200 percent of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL), and as high as 250 percent in some states.26

Loss of work-related child care benefits: In many states, child care assistance for low-income families requires documentation of work schedules, income, and care hours that match a consistent number of working hours. This requirement can prevent workers with volatile hours and inconsistent income from qualifying for subsidies.30

Find Alternate Means of Care

There are a number of alternatives to formal child care, such as staying home with your child or children, or asking a relative, friend, or neighbor to care for them. The advantages to these options include saving money and flexibility of coverage. However, informal child care situations may have less-than-optimal, long-term repercussions.

There are a number of alternatives to formal child care, such as staying home with your child or children, or asking a relative, friend, or neighbor to care for them. The advantages to these options include saving money and flexibility of coverage. However, informal child care situations may have less-than-optimal, long-term repercussions.

Lack of school readiness: While care by a stay-at-home adult may be the best option for some ALICE families, children who don’t attend preschool or other early education programs may not develop the pre-academic skills necessary for success in kindergarten and beyond. These educational gaps tend to be much more costly and difficult to close as children advance through elementary, middle, and high school.31

Possible loss of family income: If one adult in an ALICE household has to stay home to care for children, there are impacts on income stability, future earning potential, and saving for future needs. Nationwide, it is estimated that families who do not have access to affordable child care and paid family leave lose a combined $28.9 billion in wages over their lifetimes.32

Lack of school readiness: While care by a stay-at-home adult may be the best option for some ALICE families, children who don’t attend preschool or other early education programs may not develop the pre-academic skills necessary for success in kindergarten and beyond. These educational gaps tend to be much more costly and difficult to close as children advance through elementary, middle, and high school.31

Possible loss of family income: If one adult in an ALICE household has to stay home to care for children, there are impacts on income stability, future earning potential, and saving for future needs. Nationwide, it is estimated that families who do not have access to affordable child care and paid family leave lose a combined $28.9 billion in wages over their lifetimes.32

Sources

8

Annie E. Casey Foundation. (2016). Supporting Working Parents = Supporting Stronger Families. Retrieved from http://www.aecf.org/blog/supporting-working-parents-supporting-stronger-families/

Child Care Aware. (2018). The US and the High Cost of Child Care: 2018. Available from http://usa.childcareaware.org/advocacy-public-policy/resources/research/costofcare/

Li, W., Farkas, G., Duncan, G. J., Burchinal, M. R., & Vandell, D. L. (2013). Timing of High-Quality Child Care and Cognitive, Language, and Preacademic Development. Developmental Psychology. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4034459/

9

Child Care Aware. (2018). The US and the High Cost of Child Care: 2018. Available from http://usa.childcareaware.org/advocacy-public-policy/resources/research/costofcare/

10

The Pre-Kindergarten Task Force. (2017). The current state of scientific knowledge on pre-Kindergarten effects. The Brookings Institution and Duke University Center for Child and Family Policy. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/duke_prekstudy_final_4-4-17_hires.pdf

11

The National Institute for Early Education Research. The state of preschool 2017. Rutgers, Graduate School of Education. Retrieved from http://nieer.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/YB2017_Executive-Summary.pdf

12

Susman-Stillman, A., Englund, M. M., Storm, K. J., & Bailey, A.E. (2018) Understanding barriers and solutions affecting preschool attendance in low-income families. Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk (JESPAR), 23(1–2), 170–186. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10824669.2018.1434657

13

Child Care Aware. (2018). The US and the high cost of child care: 2018. Retrieved from http://usa.childcareaware.org/advocacy-public-policy/resources/research/costofcare/

14

Annie E. Casey Foundation. (2016, November 1). Supporting working parents = Supporting stronger families. Retrieved from http://www.aecf.org/blog/supporting-working-parents-supporting-stronger-families/

15

Child Trends Databank. (2019). Preschool and prekindergarten. Retrieved from https://www.childtrends.org/?indicators=preschool-and-prekindergarten

16

Child Care Aware. (2018). The US and the high cost of child care: 2018. Retrieved from http://usa.childcareaware.org/advocacy-public-policy/resources/research/costofcare/

17

Child Care Aware. (2018). The US and the high cost of child care: 2018. Retrieved from http://usa.childcareaware.org/advocacy-public-policy/resources/research/costofcare/

18

Child Care Aware. (2018). The US and the high cost of child care: 2018. Retrieved from http://usa.childcareaware.org/advocacy-public-policy/resources/research/costofcare/

19

Advisen. (2015). Safety and regulatory trends in child daycare. Retrieved from https://www.advisenltd.com/2016/01/12/safety-and-regulatory-trends-in-child-day-care/

20

Gould, E. & Cooke, T. (2015, October 6). High quality child care is out of reach for working families. Retrieved from https://www.epi.org/publication/child-care-affordability/

Child Care Aware. (2018). The US and the high cost of child care: 2018. Retrieved from http://usa.childcareaware.org/advocacy-public-policy/resources/research/costofcare/

21

Traub, A., & Ruetschlin, C. (2012). The plastic safety net. Demos. Retrieved from http://www.demos.org/sites/default/files/publications/PlasticSafetyNet-Demos.pdf

El Issa, E. (2015). 2015 American household credit card debt study. Retrieved from https://www.nerdwallet.com/blog/average-credit-card-debt-household/

22

The Pre-Kindergarten Task Force. (2017). The current state of scientific knowledge on pre-Kindergarten effects. The Brookings Institution and Duke University Center for Child and Family Policy. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/duke_prekstudy_final_4-4-17_hires.pdf

23

The National Institute for Early Education Research. The state of preschool 2017. Rutgers, Graduate School of Education. Retrieved from http://nieer.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/YB2017_Executive-Summary.pdf

24

The National Institute for Early Education Research. The state of preschool 2017. Rutgers, Graduate School of Education. Retrieved from http://nieer.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/YB2017_Executive-Summary.pdf

25

The National Institute for Early Education Research. The state of preschool 2017. Rutgers, Graduate School of Education. Retrieved from http://nieer.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/YB2017_Executive-Summary.pdf

26

Child Care Aware of America. (n.d.). Paying for child care. Retrieved from https://www.childcareaware.org/help-paying-child-care-federal-and-state-child-care-programs/

Hahn, H., Rohacek, F. & Isaacs, J. (2018). Improving child care subsidy programs. Urban Institute. Retrieved from https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/96376/improving_child_care_subsidy_programs.pdf

Schulman, K., & Blank, H. (2016). Red light green light: State child care assistance policies 2016. National Women’s Law Center. Retrieved from https://nwlc.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/NWLC-State-Child-Care-Assistance-Policies-2016-final.pdf

27

Annie E. Casey Foundation. (2016, November 1). Supporting working parents = Supporting stronger families. Retrieved from http://www.aecf.org/blog/supporting-working-parents-supporting-stronger-families/

28

Schulman, K., & Blank, H. (2017, October). Persistent gaps: State child care assistance policies 2017. National Women's Law Center. Retrieved from https://nwlc.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/NWLC-State-Child-Care-Assistance-Policies-2017.pdf

29

American Psychological Association. (2019). Education and socioeconomic status. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/pi/ses/resources/publications/education

Aikens, N. L., & Barbarin, O. (2008). Socioeconomic differences in reading trajectories: The contribution of family, neighborhood, and school contexts. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100(2), 235–251. Retrieved from https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2008-05694-001

30

Aikens, N. L., & Barbarin, O. (2008). Socioeconomic differences in reading trajectories: The contribution of family, neighborhood, and school contexts. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100(2), 235–251. Retrieved from https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2008-05694-001

31

The Pre-Kindergarten Task Force. (2017). The current state of scientific knowledge on pre-Kindergarten effects. The Brookings Institution and Duke University Center for Child and Family Policy. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/duke_prekstudy_final_4-4-17_hires.pdf

U.S. Census Bureau. (2018, September 12). Income and poverty in the United States: 2017. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2018/demo/p60-263.html

Center on Society and Health. (2015). Why education matters to health: Exploring the causes. Retrieved from https://societyhealth.vcu.edu/work/the-projects/why-education-matters-to-health-exploring-the-causes.html

32

Child Care Aware. (2018). The US and the high cost of child care: 2018. Retrieved from http://usa.childcareaware.org/advocacy-public-policy/resources/research/costofcare/

33

Child Care Aware. (2018). The US and the high cost of child care: 2018. Retrieved from http://usa.childcareaware.org/advocacy-public-policy/resources/research/costofcare/